# Design Kafka

# Overview

# Goal

Design a distributed messaging system that can reliably transfer a high throughput of messages between different entities.

# Background

One of the common challenges among distributed systems is handling a continuous influx of data from multiple sources. Imagine a log aggregation service that is receiving hundreds of log entries per second from different sources. The function of this log aggregation service is to store these logs on disk at a shared server and also build an index so that the logs can be searched later. A few challenges of this service are:

- How will the log aggregation service handle a spike of messages? If the service can handle (or buffer) 500 messages per second, what will happen if it starts receiving a higher number of messages per second? If we decide to have multiple instances of the log aggregation service, how do we divide the work among these instances?

- How can we receive messages from different types of sources? The sources producing (or consuming) these logs need to decide upon a common protocol and data format to send log messages to the log aggregation service. This leads us to a strongly coupled architecture between the producer and consumer of the log messages.

- What will happen to the log messages if the log aggregation service is down or unresponsive for some time?

To efficiently manage such scenarios, distributed systems depend upon a messaging system.

# What is a messaging system?

A messaging system is responsible for transferring data among services, applications, processes, or servers. Such a system helps decouple different parts of a distributed system by providing an asynchronous way of transferring messaging between the sender and the receiver. Hence, all senders (or producers) and receivers (or consumers) focus on the data/message without worrying about the mechanism used to share the data.

Messaging system

There are two common ways to handle messages: Queuing and Publish-Subscribe.

# Queue

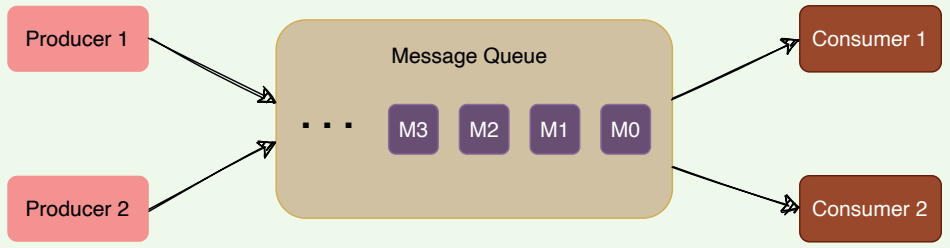

In the queuing model, messages are stored sequentially in a queue. Producers push messages to the rear of the queue, and consumers extract the messages from the front of the queue

A particular message can be consumed by a maximum of one consumer only. Once a consumer grabs a message, it is removed from the queue such that the next consumer will get the next message. This is a great model for distributing message-processing among multiple consumers. But this also limits the system as multiple consumers cannot read the same message from the queue.

Message consumption in a message queue

# Publish-subscribe messaging system

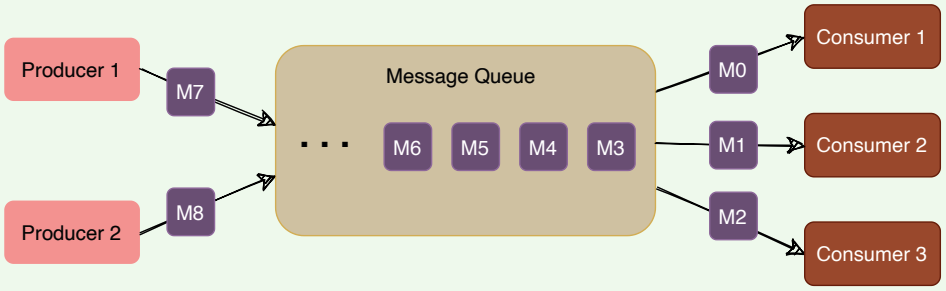

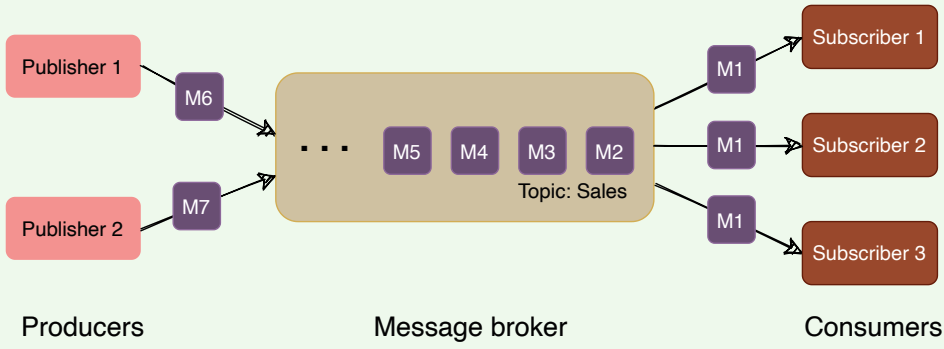

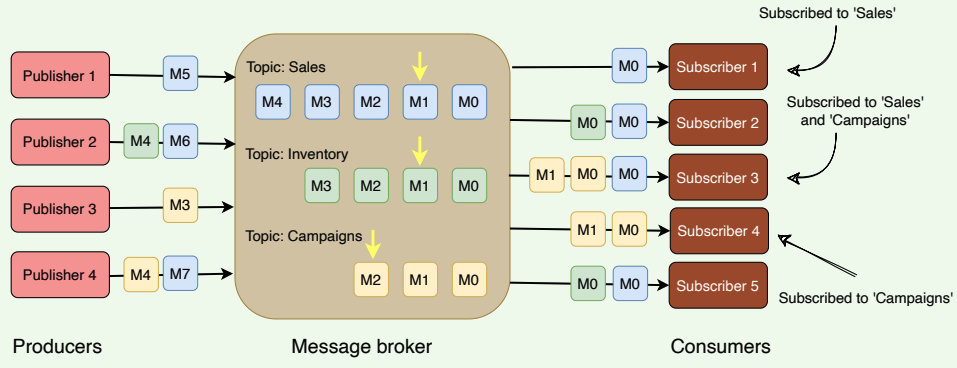

In the pub-sub (short for publish-subscribe) model, messages are divided into topics. A publisher (or a producer) sends a message to a topic that gets stored in the messaging system under that topic. Subscribers (or the consumer) subscribe to a topic to receive every message published to that topic. Unlike the Queuing model, the pub-sub model allows multiple consumers to get the same message; if two consumers subscribe to the same topic, they will receive all messages published to that topic.

Pub-sub messaging system

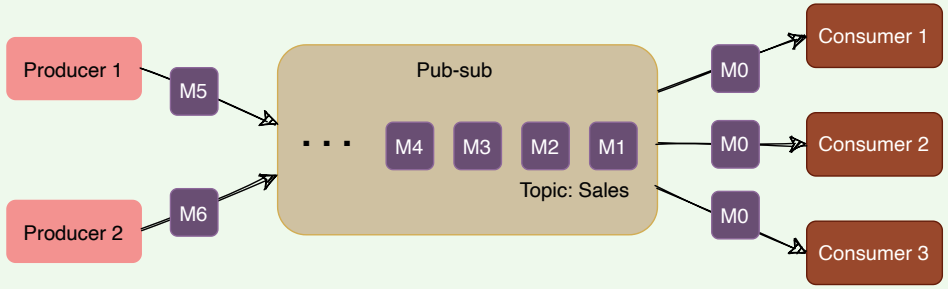

The messaging system that stores and maintains the messages is commonly known as the message broker. It provides a loose coupling between publishers and subscribers, or producers and consumers of data.

Message broker

The message broker stores published messages in a queue, and subscribers read them from the queue. Hence, subscribers and publishers do not have to be synchronized. This loose coupling enables subscribers and publishers to read and write messages at different rates.

The messaging system’s ability to store messages provides fault-tolerance, so messages do not get lost between the time they are produced and the time they are consumed.

To summarize, a message system is deployed in an application stack for the following reasons:

- Messaging buffering. To provide a buffering mechanism in front of processing (i.e., to deal with temporary incoming message spikes that are greater than what the processing app can deal with). This enables the system to safely deal with spikes in workloads by temporarily storing data until it is ready for processing.

- Guarantee of message delivery. Allows producers to publish messages with assurance that the message will eventually be delivered if the consuming application is unable to receive the message when it is published.

- Providing abstraction. A messaging system provides an architectural separation between the consumers of messages and the applications producing the messages.

- Enabling scale. Provides a flexible and highly configurable architecture that enables many producers to deliver messages to multiple consumers.

# Kafka: Introduction

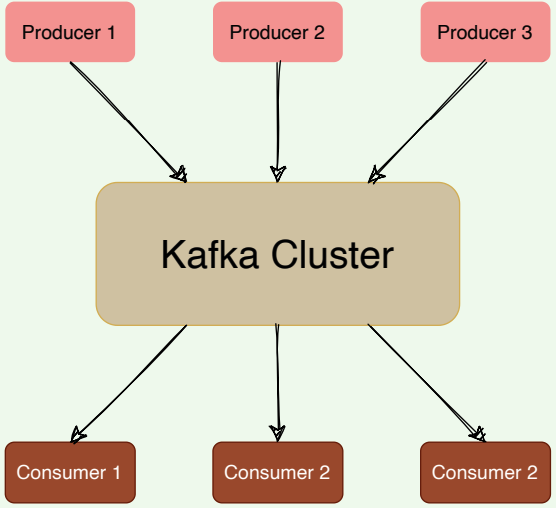

Apache Kafka is an open-source publish-subscribe-based messaging system (Kafka can work as a message queue too). It is distributed, durable, fault-tolerant, and highly scalable by design. Fundamentally, it is a system that takes streams of messages from applications known as producers, stores them reliably on a central cluster (containing a set of brokers), and allows those messages to be received by applications (known as consumers) that process the messages.

A high-level view of Kafka

# Background

Kafka was created at LinkedIn around 2010 to track various events, such as page views, messages from the messaging system, and logs from various services. Later, it was made open-source and developed into a comprehensive system which is used for:

- Reliably storing a huge amount of data.

- Enabling high throughput of message transfer between different entities.

- Streaming real-time data.

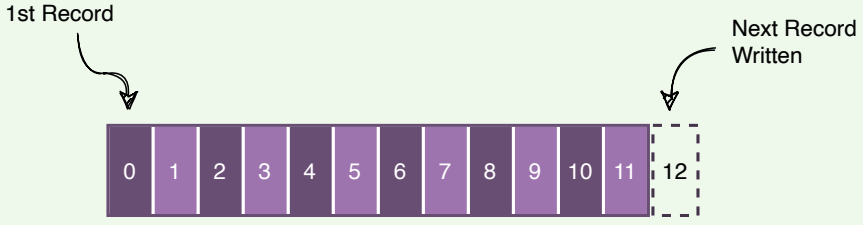

At a high level, we can call Kafka a distributed Commit Log. A Commit Log (also known as a Write-Ahead log or a Transactions log) is an append-only data structure that can persistently store a sequence of records. Records are always appended to the end of the log, and once added, records cannot be deleted or modified. Reading from a commit log always happens from left to right (or old to new).

Kafka as a write-ahead log

Kafka stores all of its messages on disk. Since all reads and writes happen in sequence, Kafka takes advantage of sequential disk reads

# Kafka use cases

Kafka can be used for collecting big data and real-time analysis. Here are some of its top use cases:

- Metrics: Kafka can be used to collect and aggregate monitoring data. Distributed services can push different operational metrics to Kafka servers. These metrics can then be pulled from Kafka to produce aggregated statistics.

- Log Aggregation: Kafka can be used to collect logs from multiple sources and make them available in a standard format to multiple consumers.

- Stream processing: Kafka is quite useful for use cases where the collected data undergoes processing at multiple stages. For example, the raw data consumed from a topic is transformed, enriched, or aggregated and pushed to a new topic for further consumption. This way of data processing is known as stream processing.

- Commit Log: Kafka can be used as an external commit log for any distributed system. Distributed services can log their transactions to Kafka to keep track of what is happening. This transaction data can be used for replication between nodes and also becomes very useful for disaster recovery, for example, to help failed nodes to recover their states.

- Website activity tracking: One of Kafka’s original use cases was to build a user activity tracking pipeline. User activities like page clicks, searches, etc., are published to Kafka into separate topics. These topics are available for subscription for a range of use cases, including realtime processing, real-time monitoring, or loading into Hadoop (opens new window) or data warehousing systems for offline processing and reporting.

- Product suggestions: Imagine an online shopping site like amazon.com (opens new window), which offers a feature of ‘similar products’ to suggest lookalike products that a customer could be interested in buying. To make this work, we can track every consumer action, like search queries, product clicks, time spent on any product, etc., and record these activities in Kafka. Then, a consumer application can read these messages to find correlated products that can be shown to the customer in real-time. Alternatively, since all data is persistent in Kafka, a batch job can run overnight on the ‘similar product’ information gathered by the system, generating an email for the customer with product suggestions.

# High-level Architecture

# Kafka common terms

# Brokers

A Kafka server is also called a broker. Brokers are responsible for reliably storing data provided by the producers and making it available to the consumers.

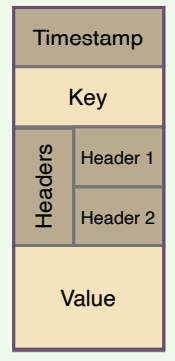

# Records

A record is a message or an event that gets stored in Kafka. Essentially, it is the data that travels from producer to consumer through Kafka. A record contains a key, a value, a timestamp, and optional metadata headers.

Kafka message

# Topics

Kafka divides its messages into categories called Topics. In simple terms, a topic is like a table in a database, and the messages are the rows in that table.

- Each message that Kafka receives from a producer is associated with a topic.

- Consumers can subscribe to a topic to get notified when new messages are added to that topic.

- A topic can have multiple subscribers that read messages from it.

- In a Kafka cluster, a topic is identified by its name and must be unique.

Messages in a topic can be read as often as needed — unlike traditional messaging systems, messages are not deleted after consumption. Instead, Kafka retains messages for a configurable amount of time or until a storage size is exceeded. Kafka’s performance is effectively constant with respect to data size, so storing data for a long time is perfectly fine.

Kafka topics

# Producers

Producers are applications that publish (or write) records to Kafka.

# Consumers

Consumers are the applications that subscribe to (read and process) data from Kafka topics. Consumers subscribe to one or more topics and consume published messages by pulling data from the brokers.

In Kafka, producers and consumers are fully decoupled and agnostic of each other, which is a key design element to achieve the high scalability that Kafka is known for. For example, producers never need to wait for consumers.

# High-level architecture

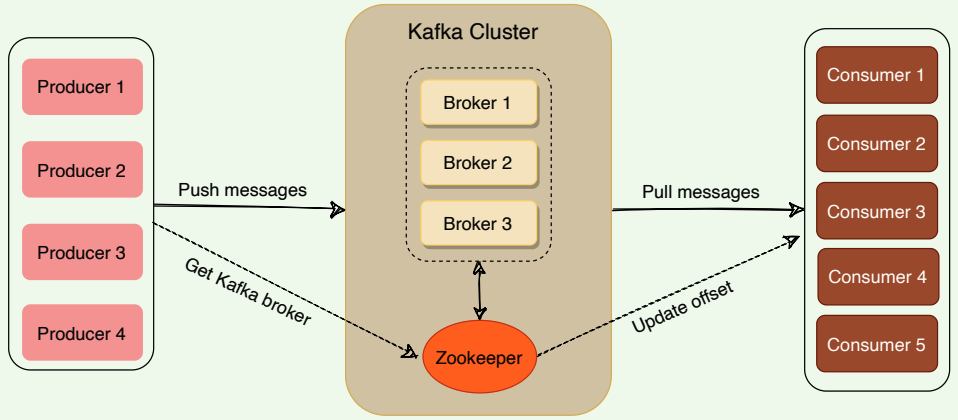

At a high level, applications (producers) send messages to a Kafka broker, and these messages are read by other applications called consumers. Messages get stored in a topic, and consumers subscribe to the topic to receive new messages.

# Kafka cluster

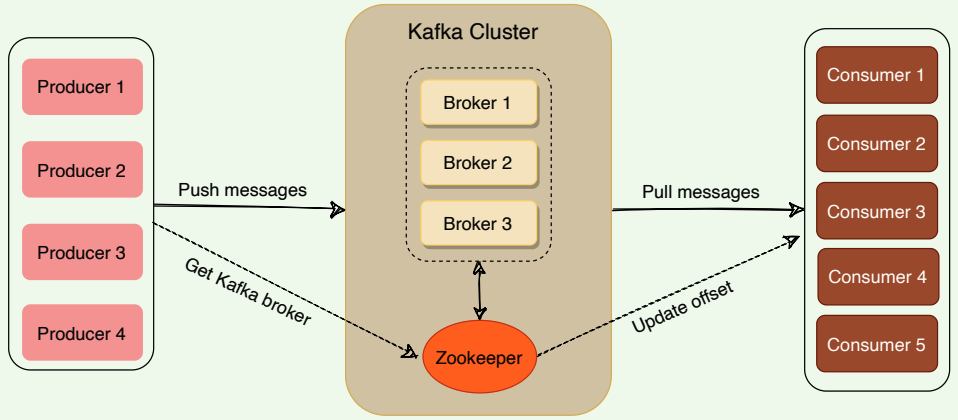

Kafka is run as a cluster of one or more servers, where each server is responsible for running one Kafka broker.

# ZooKeeper

ZooKeeper is a distributed key-value store and is used for coordination and storing configurations. It is highly optimized for reads. Kafka uses ZooKeeper to coordinate between Kafka brokers; ZooKeeper maintains metadata information about the Kafka cluster. We will be looking into this in detail later.

High level architecture of Kafka

# Kafka: Deep Dive

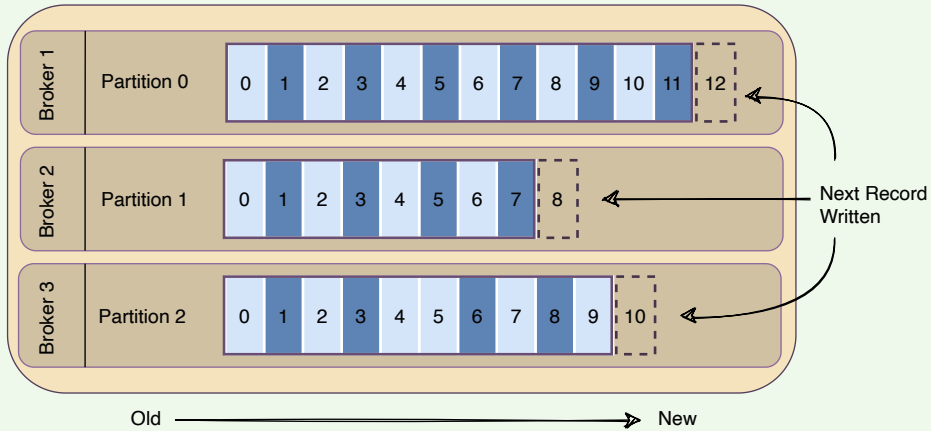

Kafka is simply a collection of topics. As topics can get quite big, they are split into partitions of a smaller size for better performance and scalability.

# Topic partitions

Kafka topics are partitioned, meaning a topic is spread over a number of ‘fragments’. Each partition can be placed on a separate Kafka broker. When a new message is published on a topic, it gets appended to one of the topic’s partitions. The producer controls which partition it publishes messages to based on the data. For example, a producer can decide that all messages related to a particular ‘city’ go to the same partition.

Essentially, a partition is an ordered sequence of messages. Producers continually append new messages to partitions. Kafka guarantees that all messages inside a partition are stored in the sequence they came in.

Ordering of messages is maintained at the partition level, not across the topic.

A topic having three partitions residing on three brokers

- A unique sequence ID called an offset gets assigned to every message that enters a partition. These numerical offsets are used to identify every message’s sequential position within a topic’s partition.

- Offset sequences are unique only to each partition. This means, to locate a specific message, we need to know the Topic, Partition, and Offset number.

- Producers can choose to publish a message to any partition. If ordering within a partition is not needed, a round-robin partition strategy can be used, so records get distributed evenly across partitions.

- Placing each partition on separate Kafka brokers enables multiple consumers to read from a topic in parallel. That means, different consumers can concurrently read different partitions present on separate brokers.

- Placing each partition of a topic on a separate broker also enables a topic to hold more data than the capacity of one server.

- Messages once written to partitions are immutable and cannot be updated.

- A producer can add a ‘key’ to any message it publishes. Kafka guarantees that messages with the same key are written to the same partition.

- Each broker manages a set of partitions belonging to different topics

Kafka follows the principle of a dumb broker and smart consumer. This means that Kafka does not keep track of what records are read by the consumer. Instead, consumers, themselves, poll Kafka for new messages and say what records they want to read. This allows them to increment/decrement the offset they are at as they wish, thus being able to replay and reprocess messages. Consumers can read messages starting from a specific offset and are allowed to read from any offset they choose. This also enables consumers to join the cluster at any point in time.

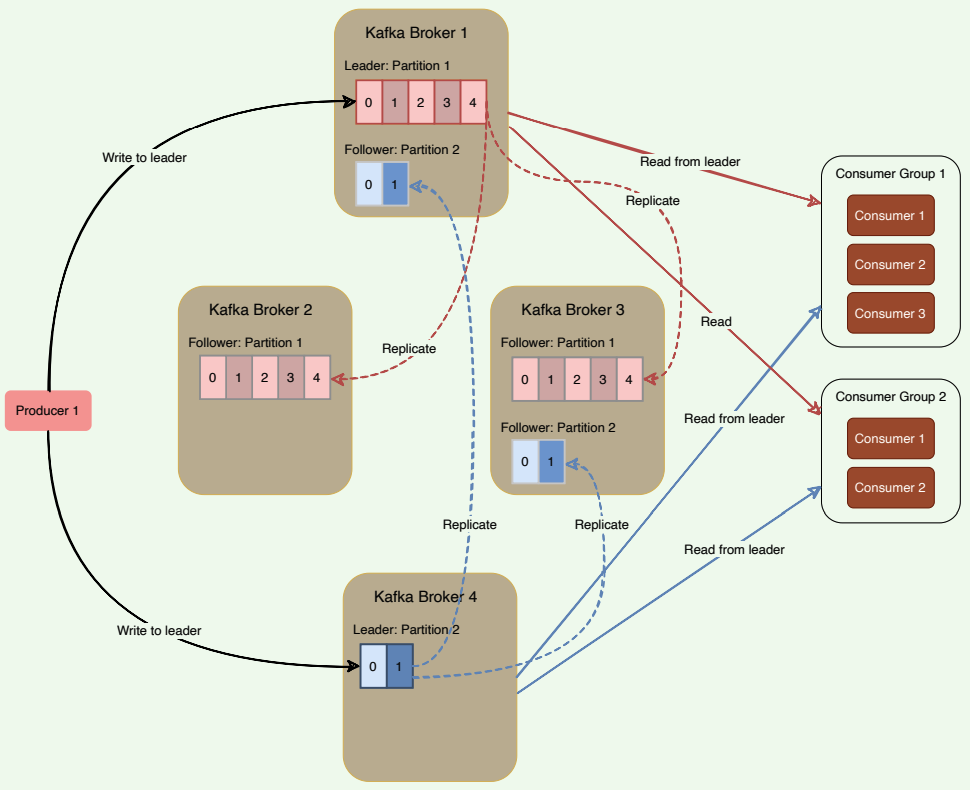

Every topic can be replicated to multiple Kafka brokers to make the data fault-tolerant and highly available. Each topic partition has one leader broker and multiple replica (follower) brokers.

# Leader

A leader is the node responsible for all reads and writes for the given partition. Every partition has one Kafka broker acting as a leader.

# Follower

To handle single point of failure, Kafka can replicate partitions and distribute them across multiple broker servers called followers. Each follower’s responsibility is to replicate the leader’s data to serve as a ‘backup’ partition. This also means that any follower can take over the leadership if the leader goes down.

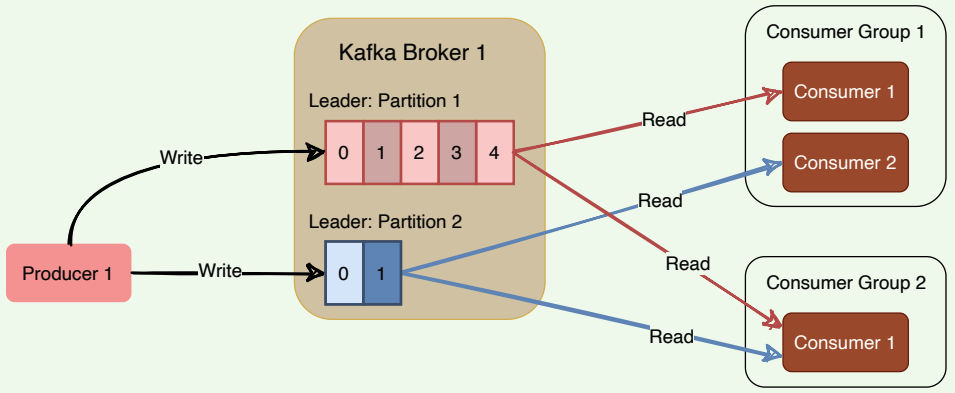

In the following diagram, we have two partitions and four brokers. Broker 1 is the leader of Partition 1 and follower of Partition 2 . Consumers

work together in groups to process messages efficiently. More details on

consumer groups later.

Leader and followers of partitions

Kafka stores the location of the leader of each partition in ZooKeeper. As all writes/reads happen at/from the leader, producers and consumers directly talk to ZooKeeper to find a partition leader.

# In-sync replicas

An in-sync replica (ISR) is a broker that has the latest data for a given partition. A leader is always an in-sync replica. A follower is an in-sync replica only if it has fully caught up to the partition it is following. In other words, ISRs cannot be behind on the latest records for a given partition. Only ISRs are eligible to become partition leaders. Kafka can choose the minimum number of ISRs required before the data becomes available for consumers to read.

# High-water mark

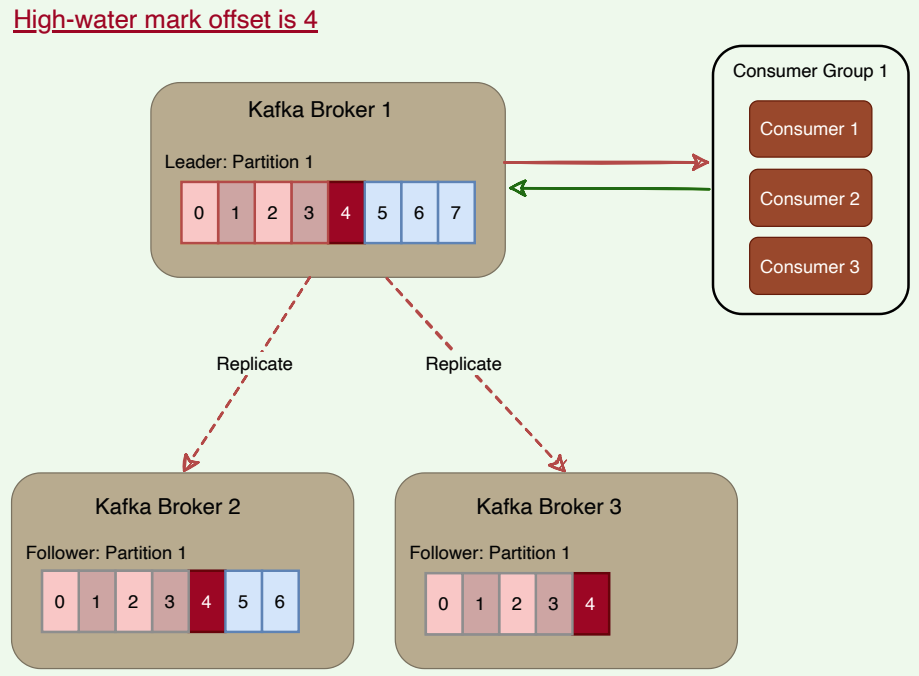

To ensure data consistency, the leader broker never returns (or exposes) messages which have not been replicated to a minimum set of ISRs. For this, brokers keep track of the high-water mark, which is the highest offset that all ISRs of a particular partition share. The leader exposes data only up to the high-water mark offset and propagates the high-water mark offset to all followers. Let’s understand this with an example.

In the figure below, the leader does not return messages greater than offset ‘4’, as it is the highest offset message that has been replicated to all follower brokers.

High-water mark offset

If a consumer reads the record with offset ‘7’ from the leader (Broker 1), and later, if the current leader fails, and one of the followers becomes the leader before the record is replicated to the followers, the consumer will not be able to find that message on the new leader. The client, in this case, will experience a non-repeatable read. Because of this possibility, Kafka brokers only return records up to the high-water mark.

# Consumer Groups

A consumer group is basically a set of one or more consumers working together in parallel to consume messages from topic partitions. Messages are equally divided among all the consumers of a group, with no two consumers receiving the same message.

# Distributing partitions to consumers within a consumer group

Kafka ensures that only a single consumer reads messages from any partition within a consumer group. In other words, topic partitions are a unit of parallelism – only one consumer can work on a partition in a consumer group at a time. If a consumer stops, Kafka spreads partitions across the remaining consumers in the same consumer group. Similarly, every time a consumer is added to or removed from a group, the consumption is rebalanced within the group.

How Kafka distributes partitions to consumers within a consumer group

Consumers pull messages from topic partitions. Different consumers can be responsible for different partitions. Kafka can support a large number of consumers and retain large amounts of data with very little overhead. By using consumer groups, consumers can be parallelized so that multiple consumers can read from multiple partitions on a topic, allowing a very high message processing throughput. The number of partitions impacts consumers’ maximum parallelism, as there cannot be more consumers than partitions.

Kafka stores the current offset per consumer group per topic per partition, as it would for a single consumer. This means that unique messages are only sent to a single consumer in a consumer group, and the load is balanced across consumers as equally as possible.

When the number of consumers exceeds the number of partitions in a topic, all new consumers wait in idle mode until an existing consumer unsubscribes from that partition. Similarly, as new consumers join a consumer group, Kafka initiates a rebalancing if there are more consumers than partitions. Kafka uses any unused consumers as failovers.

Here is a summary of how Kafka manages the distribution of partitions to consumers within a consumer group:

- Number of consumers in a group = number of partitions: each consumer consumes one partition.

- Number of consumers in a group > number of partitions: some consumers will be idle.

- Number of consumers in a group < number of partitions: some consumers will consume more partitions than others.

# Kafka Workow

Kafka provides both pub-sub and queue-based messaging systems in a fast, reliable, persisted, fault-tolerance, and zero downtime manner. In both cases, producers simply send the message to a topic, and consumers can choose any one type of messaging system depending on their need. Let us follow the steps in the next section, to understand how the consumer can choose the messaging system of their choice.

# Kafka workflow as pub-sub messaging

Following is the stepwise workflow of the Pub-Sub Messaging:

- Producers publish messages on a topic.

- Kafka broker stores messages in the partitions configured for that particular topic. If the producer did not specify the partition in which the message should be stored, the broker ensures that the messages are equally shared between partitions. If the producer sends two messages and there are two partitions, Kafka will store one message in the first partition and the second message in the second partition.

- Consumer subscribes to a specific topic.

- Once the consumer subscribes to a topic, Kafka will provide the current offset of the topic to the consumer and also saves that offset in the ZooKeeper.

- Consumer will request Kafka at regular intervals for new messages.

- Once Kafka receives the messages from producers, it forwards these messages to the consumer.

- Consumer will receive the message and process it.

- Once the messages are processed, the consumer will send an acknowledgment to the Kafka broker.

- Upon receiving the acknowledgment, Kafka increments the offset and updates it in the ZooKeeper. Since offsets are maintained in the

- ZooKeeper, the consumer can read the next message correctly, even during broker outages.

- The above flow will repeat until the consumer stops sending the request.

- Consumers can rewind/skip to the desired offset of a topic at any time and read all the subsequent messages.

# Kafka workflow for consumer group

Instead of a single consumer, a group of consumers from one consumer group subscribes to a topic, and the messages are shared among them. Let us check the workflow of this system:

- Producers publish messages on a topic.

- Kafka stores all messages in the partitions configured for that particular topic, similar to the earlier scenario.

- A single consumer subscribes to a specific topic, assume

Topic-01with Group ID asGroup-1 - Kafka interacts with the consumer in the same way as pub-sub

messaging until a new consumer subscribes to the same topic,

Topic-01, with the same Group ID asGroup-1 - Once the new consumer arrives, Kafka switches its operation to share

mode, such that each message is passed to only one of the subscribers of

the consumer group

Group-1. This message transfer is similar to queuebased messaging, as only one consumer of the group consumes a message. Contrary to queue-based messaging, messages are not removed after consumption. - This message transfer can go on until the number of consumers reaches the number of partitions configured for that particular topic.

- Once the number of consumers exceeds the number of partitions, the new consumer will not receive any message until an existing consumer unsubscribes. This scenario arises because each consumer in Kafka will be assigned a minimum of one partition. Once all the partitions are assigned to the existing consumers, the new consumers will have to wait.

# Role of ZooKeeper

A critical dependency of Apache Kafka is Apache ZooKeeper, which is a distributed configuration and synchronization service. ZooKeeper serves as the coordination interface between the Kafka brokers, producers, and consumers. Kafka stores basic metadata in ZooKeeper, such as information about brokers, topics, partitions, partition leader/followers, consumer offsets, etc.

# ZooKeeper as the central coordinator

As we know, Kafka brokers are stateless; they rely on ZooKeeper to maintain and coordinate brokers, such as notifying consumers and producers of the arrival of a new broker or failure of an existing broker, as well as routing all requests to partition leaders.

ZooKeeper is used for storing all sorts of metadata about the Kafka cluster:

- It maintains the last offset position of each consumer group per partition, so that consumers can quickly recover from the last position in case of a failure (although modern clients store offsets in a separate Kafka topic).

- It tracks the topics, number of partitions assigned to those topics, and leaders’/followers’ location in each partition.

- It also manages the access control lists (ACLs) to different topics in the cluster. ACLs are used to enforce access or authorization.

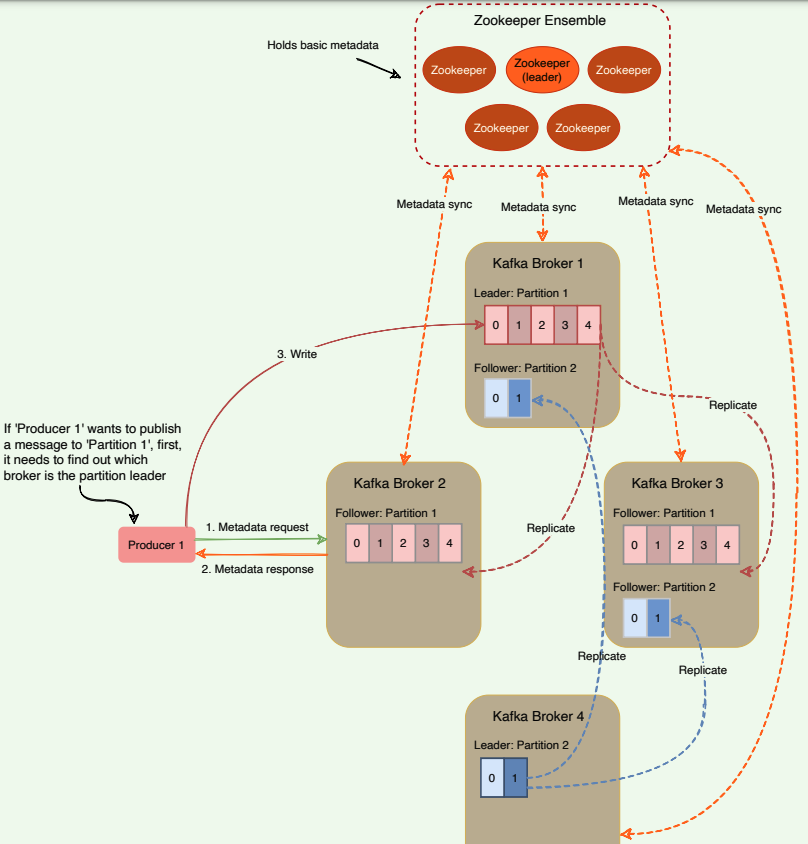

# How do producers or consumers find out who the leader of a partition is?

In the older versions of Kafka, all clients (i.e., producers and consumers) used to directly talk to ZooKeeper to find the partition leader. Kafka has moved away from this coupling, and in Kafka’s latest releases, clients fetch metadata information from Kafka brokers directly; brokers talk to ZooKeeper to get the latest metadata. In the diagram below, the producer goes through the following steps before publishing a message:

- The producer connects to any broker and asks for the leader of

‘

Partition 1’. - The broker responds with the identification of the leader broker

responsible for ‘

Partition 1’. - The producer connects to the leader broker to publish the message.

Role of ZooKeeper in Kafka

All the critical information is stored in the ZooKeeper and ZooKeeper replicates this data across its cluster, therefore, failure of Kafka broker (or ZooKeeper itself) does not affect the state of the Kafka cluster. Upon ZooKeeper failure, Kafka will always be able to restore the state once the ZooKeeper restarts after failure. Zookeeper is also responsible for coordinating the partition leader election between the Kafka brokers in case of leader failure.

# Controller Broker

Within the Kafka cluster, one broker is elected as the Controller. This Controller broker is responsible for admin operations, such as creating/deleting a topic, adding partitions, assigning leaders to partitions, monitoring broker failures, etc. Furthermore, the Controller periodically checks the health of other brokers in the system. In case it does not receive a response from a particular broker, it performs a failover to another broker. It also communicates the result of the partition leader election to other brokers in the system.

# Split brain

When a controller broker dies, Kafka elects a new controller. One of the problems is that we cannot truly know if the leader has stopped for good and has experienced an intermittent failure like a stop-the-world GC pause or a temporary network disruption. Nevertheless, the cluster has to move on and pick a new controller. If the original Controller had an intermittent failure, the cluster would end up having a so-called zombie controller. A zombie controller can be defined as a controller node that had been previously deemed dead by the cluster and has come back online. Another broker has taken its place, but the zombie controller might not know that yet. This common scenario in distributed systems with two or more active controllers (or central servers) is called split-brain.

We will have two controllers under split-brain, which will be giving out potentially conflicting commands in parallel. If something like this happens in a cluster, it can result in major inconsistencies. How do we handle this situation?

# Generation clock

Split-brain is commonly solved with a generation clock, which is simply a monotonically increasing number to indicate a server’s generation. In Kafka, the generation clock is implemented through an epoch number. If the old leader had an epoch number of ‘1’, the new one would have ‘2’. This epoch is included in every request that is sent from the Controller to other brokers. This way, brokers can now easily differentiate the real Controller by simply trusting the Controller with the highest number. The Controller with the highest number is undoubtedly the latest one, since the epoch number is always increasing. This epoch number is stored in ZooKeeper.

# Kafka Delivery Semantics

# Producer delivery semantics

As we know, a producer writes only to the leader broker, and the followers asynchronously replicate the data. How can a producer know that the data is successfully stored at the leader or that the followers are keeping up with the leader? Kafka offers three options to denote the number of brokers that must receive the record before the producer considers the write as successful:

- Async: Producer sends a message to Kafka and does not wait for acknowledgment from the server. This means that the write is considered successful the moment the request is sent out. This fire-and-forget approach gives the best performance as we can write data to Kafka at network speed, but no guarantee can be made that the server has received the record in this case.

- Committed to Leader: Producer waits for an acknowledgment from the leader. This ensures that the data is committed at the leader; it will be slower than the ‘Async’ option, as the data has to be written on disk on the leader. Under this scenario, the leader will respond without waiting for acknowledgments from the followers. In this case, the record will be lost if the leader crashes immediately after acknowledging the producer but before the followers have replicated it.

- Committed to Leader and Quorum: Producer waits for an acknowledgment from the leader and the quorum. This means the leader will wait for the full set of in-sync replicas to acknowledge the record. This will be the slowest write but guarantees that the record will not be lost as long as at least one in-sync replica remains alive. This is the strongest available guarantee.

As we can see, the above options enable us to configure our preferred tradeoff between durability and performance.

- If we would like to be sure that our records are safely stored in Kafka, we have to go with the last option – Committed to Leader and Quorum.

- If we value latency and throughput more than durability, we can choose one of the first two options. These options will have a greater chance of losing messages but will have better speed and throughput.

# Consumer delivery semantics

A consumer can read only those messages that have been written to a set of in-sync replicas. There are three ways of providing consistency to the consumer:

- At-most-once (Messages may be lost but are never redelivered): In this option, a message is delivered a maximum of one time only. Under this option, the consumer upon receiving a message, commit (or increment) the offset to the broker. Now, if the consumer crashes before fully consuming the message, that message will be lost, as when the consumer restarts, it will receive the next message from the last committed offset.

- At-least-once (Messages are never lost but maybe redelivered): Under this option, a message might be delivered more than once, but no message should be lost. This scenario occurs when the consumer receives a message from Kafka, and it does not immediately commit the offset. Instead, it waits till it completes the processing. So, if the consumer crashes after processing the message but before committing the offset, it has to reread the message upon restart. Since, in this case, the consumer never committed the offset to the broker, the broker will redeliver the same message. Thus, duplicate message delivery could happen in such a scenario.

- Exactly-once (each message is delivered once and only once): It is very hard to achieve this unless the consumer is working with a transactional system. Under this option, the consumer puts the message processing and the offset increment in one transaction. This will ensure that the offset increment will happen only if the whole transaction is complete. If the consumer crashes while processing, the transaction will be rolled back, and the offset will not be incremented. When the consumer restarts, it can reread the message as it failed to process it last time. This option leads to no data duplication and no data loss but can lead to decreased throughput.

# Kafka Characteristics

# Storing messages to disks

Kafka writes its messages to the local disk and does not keep anything in RAM. Disks storage is important for durability so that the messages will not disappear if the system dies and restarts. Disks are generally considered to be slow. However, there is a huge difference in disk performance between random block access and sequential access. Random block access is slower because of numerous disk seeks, whereas the sequential nature of writing or reading, enables disk operations to be thousands of times faster than random access. Because all writes and reads happen sequentially, Kafka has a very high throughput.

Writing or reading sequentially from disks are heavily optimized by the OS, via read-ahead (prefetch large block multiples) and write-behind (group small logical writes into big physical writes) techniques.

Also, modern operating systems cache the disk in free RAM. This is called Pagecache (opens new window). Since Kafka stores messages in a standardized binary format unmodified throughout the whole flow (producer → broker → consumer), it can make use of the zero-copy (opens new window) optimization. That is when the operating system copies data from the Pagecache directly to a socket, effectively bypassing the Kafka broker application entirely.

Kafka has a protocol that groups messages together. This allows network requests to group messages together and reduces network overhead. The server, in turn, persists chunks of messages in one go, and consumers fetch large linear chunks at once.

All of these optimizations allow Kafka to deliver messages at near networkspeed.

# Record retention in Kafka

By default, Kafka retains records until it runs out of disk space. We can set time-based limits (configurable retention period), size-based limits (configurable based on size), or compaction (keeps the latest version of record using the key). For example, we can set a retention policy of three days, or two weeks, or a month, etc. The records in the topic are available for consumption until discarded by time, size, or compaction.

# Client quota

It is possible for Kafka producers and consumers to produce/consume very high volumes of data or generate requests at a very high rate and thus monopolize broker resources, cause network saturation, and, in general, deny service to other clients and the brokers themselves. Having quotas protects against these issues. Quotas become even more important in large multi-tenant clusters where a small set of badly behaved clients can degrade the user experience for the well-behaved ones.

In Kafka, quotas are byte-rate thresholds defined per client-ID . A client-ID logically identifies an application making a request. A single client-ID

can span multiple producer and consumer instances. The quota is applied

for all instances as a single entity. For example, if a client-ID has a

producer quota of 10 MB/s, that quota is shared across all instances with that

same ID.

The broker does not return an error when a client exceeds its quota but instead attempts to slow the client down. When the broker calculates that a client has exceeded its quota, it slows the client down by holding the client’s response for enough time to keep the client under the quota. This approach keeps the quota violation transparent to clients. This also prevents clients from having to implement special back-off and retry behavior.

# Kafka performance

Here are a few reasons behind Kafka’s performance and popularity:

Scalability: Two important features of Kafka contribute to its scalability.

- A Kafka cluster can easily expand or shrink (brokers can be added or removed) while in operation and without an outage.

- A Kafka topic can be expanded to contain more partitions. Because a partition cannot expand across multiple brokers, its capacity is bounded by broker disk space. Being able to increase the number of partitions and the number of brokers means there is no limit to how much data a single topic can store.

Fault-tolerance and reliability: Kafka is designed in such a way that a broker failure is detectable by ZooKeeper and other brokers in the cluster. Because each topic can be replicated on multiple brokers, the cluster can recover from broker failures and continue to work without any disruption of service.

Throughput: By using consumer groups, consumers can be parallelized, so that multiple consumers can read from multiple partitions on a topic, allowing a very high message processing throughput.

Low Latency: 99.99% of the time, data is read from disk cache and RAM; very rarely, it hits the disk.

# Summary

- Kafka provides low-latency, high-throughput, fault-tolerant publish and subscribe pipelines and can process huge continuous streams of events.

- Kafka can function both as a message queue and a publisher-subscriber system.

- At a high level, Kafka works as a distributed commit log.

- Kafka server is also called a broker. A Kafka cluster can have one or more brokers.

- A Kafka topic is a logical aggregation of messages.

- Kafka solves the scaling problem of a messaging system by splitting a topic into multiple partitions.

- Every topic partition is replicated for fault tolerance and redundancy.

- A partition has one leader replica and zero or more follower replicas.

- Partition leader is responsible for all reads and writes. Each follower's responsibility is to replicate the leader's data to serve as a 'backup' partition.

- Message ordering is preserved only on a per-partition basis (not across partitions of a topic).

- Every partition replica needs to fit on a broker, and a partition cannot be divided over multiple brokers.

- Every broker can have one or more leaders, covering different partitions and topics.

- Kafka supports a single queue model with multiple readers by enabling consumer groups.

- Kafka supports a publish-subscribe model by allowing consumers to subscribe to topics for which they want to receive messages.

- ZooKeeper functions as a centralized configuration management service.

# System design patterns

# High-water mark

To deal with non-repeatable reads and ensure data consistency, brokers keep track of the high-water mark, which is the largest offset that all ISRs of a particular partition share. Consumers can see messages only until the high watermark.

# Leader and follower

Each Kafka partition has a designated leader responsible for all reads and writes for that partition. Each follower's responsibility is to replicate the leader's data to serve as a backup' partition.

# Split-brain

To handle split-brain (where we have multiple active controller brokers), Kafka uses 'epoch number,' which is simply a monotonically increasing number to indicate a server's generation. This means if the old Controller had an epoch number of '1', the new one would have 2°. This epoch is included in every request that is sent from the Controller to other brokers.

This way, brokers can easily differentiate the real Controller by simply trusting the Controller with the highest number. This epoch number is stored in ZooKeeper.

# Segmented log

Kafka uses log segmentation to implement storage for its partitions. As Kafka regularly needs to find messages on disk for purging, a single long file could be a performance bottleneck and error-prone. For easier management and better performance, the partition is split into segments.